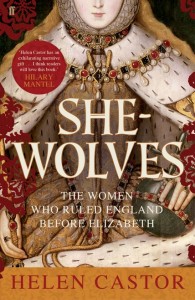

Helen Castor

Books: History | Distaff | England

She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth (2011)

This was my most recent "read before bed" book, so it took me quite awhile to finish, and I can't say that a lot of it will stick with me, but it was interesting.

This was my most recent "read before bed" book, so it took me quite awhile to finish, and I can't say that a lot of it will stick with me, but it was interesting.

The book looks at queens who attempted to rule England prior to Queen Elizabeth: Matilda, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Isabella, Margaret, and then the final section on Mary and Elizabeth

The various queens had different levels of success and failure, depending upon whether they attempted to rule in their own right, whether they attempted to rule in their own right (a failure up until Queen Mary in 1553), rule as regents for their husbands or sons, or rule by guiding their husbands and sons.

British History in school was pretty much a boring blur of names and dates, all of which ran together to be memorized for a test and the disappeared from my mind. So although many of these names were familiar, that was pretty much the extent of my knowledge. So I thought a book focusing on women might be an interesting introduction. And it was.

What is interesting is how history has painted these women–turned actions and attributes that in a man would be seen as kingly into unnatural and abominable when seen in a woman and queen. And how many of the histories that paint these women in a negative light, were written by men with an axe to grind, so they might not even accurately reflect attitudes at the time.

Freedom to act, in other words, did not mean freedom from censure and condemnation. The risk these queens ran was that their power would be perceived as a perversion of "good" womanhood, a distillation of all that was most to be feared in the unstable depths of female nature. The unease, if not outright denunciation, with which their rule was met has coalesced in the image of the she-wolf, a feral creature driven by instinct rather than reason, a sexual predator whose savagery matched that of her mate—or exceeded it, even, in the ferocity with which she defended her young.

Female "regiment"—or regimen, meaning rule or governance—was "monstrous"—that is, unnatural and abominable—because women were doubly subordinate to men, once by reason of Eve's creation from Adam's rib, and again because of her transgression in precipitating the fall from Eden.

Hard to rule with those odds stacked against you.

The first queen, Matilda, was the wife of Geoffori of Anjou (prior to that, Emperor Heinrich V), and mother of Henry II. As the daughter of Henry I and granddaughter of William the Conqueror, she believed the throne should go to her, rather than Henry's nephews. Failing that, to her sons, who she was initially able to influence.

Married at twelve (acting as queen at the age of eight), Matilda's entire live was royal politics.

Too bad Henry the II didn't listen to her regarding the appointment of Thomas Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury, an action that most people know worked out very poorly for both.

Her story looks not just as her attempts to rule, but also the social and political climate in England at the time. There was a LOT here I didn't know. For instance, the English ruling class at this time generally spoke French, not English.

Additionally, aside from Archbishop of Canterbury, the king generally appointed bishops and archbishops throughout his kingdom. It's sometimes easy to forget how intertwined the church and state were, and how the decisions of bad or weak kings could affect the church.

The second queen was Eleanor of Aquitaine, wife oh both Louis VII of France and Henry II of England, mother Richard I (the Lionheart) and grandmother of Henry III. Plus, her son Henri married the daughter of her ex-husband Louis VII of France.

First, I somehow managed never to realize that Aquitaine was an English territory well south in what is now France. And that the Duchy of Aquitaine is pretty much the same size as England.

First, I somehow managed never to realize that Aquitaine was an English territory well south in what is now France. And that the Duchy of Aquitaine is pretty much the same size as England.

Second, royalty marriages were insanely complicated with consolidation of power being the only thing of import considered.

I mean, imagine being married to Henry II.

Henry was passionately emotional, a character of extremes and contradictions. He was unpretentious, patient, and approachable, and possessed of unearthly calm in the face of crisis, yet capable of the most violent fits of rage. Court gossip (reported in 1166 to Archbishop Thomas Becket, once the king's closest friend, now estranged and in exile) described one outburst of ferocious temper that left Henry screaming on the floor, thrashing wildly and tearing at the straw stuffing of his mattress with his teeth. He loathed betrayal in others, but was notorious for his willingness to break his own word without a second thought. He could be fierce or gentle, harsh or generous; and he contrived (without apparent contrivance) to be simultaneously an immovable object and an irresistible force.

THAT sounds like lots of fun. I mean, this guy pretty much exiled his own wife back to Aquitaine.

Eleanor was far more successful at guiding the kingdom than Matilda, through her influence on several (but not all) of her sons. But she was still never allowed to hold power outside of her own duchy.

Isabella of France, daughter of Philippe III of France, was married to Edward II of England, and mother of Edward III.

She had a pretty miserable marriage, with her husband taking up first with Piers Gaveston, and later, more disastrously, with Hugh Despenser. Isabella was all but ignored by Edward II who allowed first Gaveston (who was merely a pretty distraction) and then Gaveston, who was a power-hungry tyrant, to advise him.

Unfortunately, once Isabella helped dethrone Edward II, her own relationship with Roger Mortimer was little better, and pretty much ruined her influence with her son, Edward III.

The fourth queen was Margaret of Anjou, wife of Henry VI. Her husband was never more than a pawn for whoever possessed him at the time. This led to a horrible mess, with power shuffling back and forth among various lords and nobles who physically held the kind and made proclamations and laws through him.

Henry was not a tyrant. Instead, he simply smiled and nodded and expressed mild amazement at the workings of the world—"St. John, grant mercy!" was a favourite exclamation—before agreeing to whatever proposal was presently placed before him.

Henry's … lack of intellectual prowess is what led to the Wars of the Roses, and caused such a huge upheaval for England (though perhaps not quite as much Isabella caused).

I don't think I completely understand The Wars of the Roses (and all the other wars), but it is fascinating to see how the role of women changed over time.

It's an interesting book, and well done, though I'm not sure if I would have quite enjoyed this as something other than bed-time reading material.

Published by HarperCollins

Rating: 7/10