Tom Standage

Books: History | Food & Drink

A History of the World in 6 Glasses (2005), An Edible History of Humanity (2009)

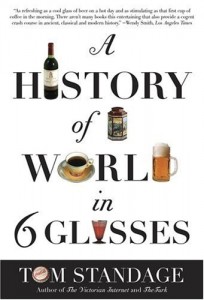

A History of the World in 6 Glasses (2005)

I got this as a kindle deal, and was absolutely delighted by it. It's a look at how six beverages–beer, wine, liquor, coffee, tea, and Coca Cola–changed the world.

I got this as a kindle deal, and was absolutely delighted by it. It's a look at how six beverages–beer, wine, liquor, coffee, tea, and Coca Cola–changed the world.

There were so very many fascinating historical tidbits, I'm afraid that on multiple occasions I regaled my walking partner with facts she probably already knew, but I did not.

For example:

Beer:

Ancient beer had grains, chaff, and other debris floating on its surface, so a straw was necessary to avoid swallowing them.

Wine:

The distinction between beer in northern Europe and wine in the south persists to this day. Modern European drinking patterns crystallized during the middle of the first millennium and were largely determined by the reach of Greek and Roman influences.

Liquor:

Distilled drinks, alongside firearms and infectious diseases, helped to shape the modern world by helping the inhabitants of the Old World to establish themselves as rulers of the New World. Spirits played a role in the enslavement and displacement of millions of people, the establishment of new nations, and the subjugation of indigenous cultures.

Coffee:

Coffee's opponents tried to argue that any change in the drinker's physical or mental state was grounds on which to ban coffee. …Indeed, it was not so much coffee's effects on the drinker but the circumstances in which it was consumed that worried the authorities, for coffeehouses were hotbeds of gossip, rumor, political debate, and satirical discussion. They were also popular venues for chess and backgammon, which were regarded as morally dubious.

Backgammon and chess were morally dubious?!

Shortly before his death in 1605, Pope Clement VIII was asked to state the Catholic church's position on coffee. … Coffee's religious opponents argued that coffee was evil: They contended that since Muslims were unable to drink wine, the holy drink of Christians, the devil had punished them with coffee instead.

Well, that's how I feel about coffee.

Tea on the other hand:

The prosperity of the period and the surge in population were helped along by the widespread adoption of the custom of drinking tea. Its powerful antiseptic properties meant it was safer to drink than previous beverages such as rice or millet beer, even if the water was not properly boiled during preparation. Modern research has found that the phenolics (tannic acid) in tea can kill the bacteria that cause cholera, typhoid, and dysentery.

There is so much on the British East India company and tea, I may make a blog post out of it.

The political power of the British East India Company, the organization that supplied Britain's tea, was vast. At its height the company generated more revenue than the British government and ruled over far more people, while the duty on the tea it imported accounted for as much as 10 percent of government revenue.

…

(The American colonists) resented the way the government was handing the East India Company a monopoly on the retailing of tea. What would be next? "The East India Company, if once they get Footing in this (once) happy Country, will leave no Stone unturned to become your Masters," declared a broadside published in Philadelphia in December 1773. "They have a designing, depraved and despotic Ministry to assist and support them. They themselves are well versed in Tyranny, Plunder, Oppression and Bloodshed. . . . Thus they have enriched themselves, thus they are become the most powerful Trading company in the Universe."

So essentially, the Boston Tea Party was not a protest against the British Government as much as it was a protest against the British East India Company.

Funny how the modern "tea party" misses that this protest was against big business, not big government. And that doesn't even begin to look at the British East India Company's involvement with the opium trade. (And by involvement, I mean, creating and running.)

And then finally Coca-Cola.

Until 1895 (Coca-Cola) was still being sold as a primarily medicinal product— described as a "Sovereign Remedy for Headache"...

Selling it simply as a refreshing drink, in contrast, gave it universal appeal; not everyone is ill, but everyone is thirsty at one time or another...

In 1898 a tax was imposed on patent medicines, a category which was initially deemed to include Coca-Cola. The company fought the decision and ultimately won exemption from the tax…

…(Harvey Washington Wiley, a government scientist) put Coca-Cola on trial in 1911, in a federal case titled The United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of CocaCola. In court, religious fundamentalists railed against the evils of Coca-Cola, blaming its caffeine content for promoting sexual transgressions…

Did I at all pique your interest? I hope so, because this is a fabulous book, and one well worth reading.

Published by Walker Books

Rating: 10/10

An Edible History of Humanity (2009)

Forever ago I read a History of the World in 6 Glasses,

and found it interesting, so I picked up this, let it languish for

awhile, and then finally decided to settle down and read it.

Forever ago I read a History of the World in 6 Glasses,

and found it interesting, so I picked up this, let it languish for

awhile, and then finally decided to settle down and read it.

I found many of the historical bits interesting.

It is only within the past 11,000 years or so that humans began to cultivate food deliberately.

(H)umans domesticated animals for the purpose of providing food, starting with sheep and goats in the Near East around 8000 B.C. and followed by cattle and pigs soon afterward. (Pigs were independently domesticated in China at roughly the same time, and the chicken was domesticated in southeast Asia around 6000 B.C.)

There is also some mythology mixed in, that of course fascinated me.

But the historical bits were really what I liked, especially when they upended some of the things I thought I knew.

(W)hy humans switched from hunting and gathering to farming is one of the oldest, most complex, and most important questions in human history. It is mysterious because the switch made people significantly worse off, from a nutritional perspective and in many other ways.

This bit gets really complicated, yet well explained, and was probably worth the price of the book.

He then posits how farming essentially created governments and wealth and (eventually) power imbalances. How it created trade and nations. And how it created the abomination that was the slave trade.

Nobody would do such dangerous and repetitive work at the low salaries planters were offering, which is why the planters relied on slave labor.

This pattern is actually one that should sound familiar to the modern ear, except instead of slaves, it's illegal immigrants who live in horrible conditions so they can send wages home and make a better life there.

The story then got fairly dry, when we get into Malthus and population growth, but got interesting again when it turned to war and transportation.

Alexander's rule of thumb, which was still valid centuries later, was that an army could only forage within a four-day radius of its camp, because a pack animal devours its own load within eight days.

The way that warfare was shaped and controlled by food supplies and transportation is one of the most interesting parts of the book, especially when he lays out how supply lines affected the outcome of the American Revolutionary war.

The final chapters were again rather dry, as they focused on Malthus and population growth. Especially considering that they were reiterating something I already knew. But the earlier chapters were well-worth putting up with the slower bits.

Publisher: Bloomsbury USA

Rating: 7.5/10